Introduction

I have taken the adjectives hypnotising and mesmerising to be very similar, and possibly even sharing the same meaning, and as such many of the examples in this entry could fit into either adjective. However, I have personally experienced some degree of altered states resulting from exposure to many of the examples provided, so perhaps they could all be considered hypnotic; I will continue to use this adjective to describe each example.

My interest in hypnotic experiences has origins in my musical taste; notably, my interest in minimalist and repetitive music. Creating music and audiovisual media with the intention of either inducing altered states, or illusions/hallucinations—without the use of psychedelic drugs—has been a key goal in my own work, which takes inspiration from many of the following examples. As such, my interpretation of hypnotic is anything capable of generating illusions or altered states.

Auditory examples

Lorenzo Senni – Superimpositions

Lorenzo Senni’s music is often referred to as “deconstructed trance”, and Superimpositions is a good example of this. Unrelenting in its repetition, a single chord progression pattern slowly iterates in timbre over nearly six minutes. The use of heavily gated, staccato chords creates “gaps” in the sound, which contributes greatly to the hypnotic experience.

Steve Reich – Music for 18 Musicians

Any of Steve Reich’s compositions could be considered hypnotic, but Music for 18 Musicians is a particularly good example. The many interleaving, phased patterns affect the listener’s perception of rhythm and time, creating a kind of auditory illusion, especially evident in the later movements, where the sound is almost similar to digital timestretching or granular synthesis. Listening intently to the entire composition, the repeated pulse tends to fade into the background, and as such the ending creates a sense of emptiness.

Autechre – all end

Autechre’s NTS Sessions album series is a four-part, eight hour collection of extended electronic pieces. The fourth part’s closing track, all end, is an hour-long, time-stretched string sound, providing a hypnotic experience through a very slow moving soundscape. Much like Music for 18 Musicians, listening to the entire piece results in the ending feeling “empty”. For me, the feeling of something being subtracted from reality at the end of such long-form, slow moving pieces is an important part of the experience.

Pan Sonic – Muuntaja

The use of short, repeating patterns in minimal techno can be considered hypnotic. Pan Sonic’s Muuntaja is an intense example of such repetition, with very slow movement occuring throughout the piece, punctuated by an abrupt change in the rhythm (7:42 in the above video), which can lead to the listener being “snapped out” of any potential hypnotic states. Additionally, the high pitched tone introduced at 1:59 is another example of a sonic element “fading into the background” and creating a jarring transition when it finally stops at 9:47.

Liturgy – Generation

While many would not find the metal music genre hypnotic, Liturgy’s composition Generation fits the description through its use of unrelenting, repetitive patterns. The use of techniques such as rhythmic phasing and slow iteration show parallels to minimalist composition. Texturally, much like the other examples shown so far, the ending of the piece is a jarring transition into silence, due to the constant intensity suddenly coming to a stop. This is perhaps the most powerful use of such an auditory device (if it can even be called that) in all of the examples shown.

Audiovisual examples

Laurie Anderson – O Superman

Similar to the Steve Reich example, O Superman uses a repeating pulse throughout the piece, and on its own is quite hypnotic through the use of minimalist melodic content and repetition. The music video extends this, using sparse shots of Anderson often performing slow, repeating hand movements (and sign language at one point), and often showing a simple closeup of her face. My personal experience with the music video is through watching it late at night, which adds to the hypnotising experience.

The Chemical Brothers – Star Guitar

Michel Gondry’s music video for Star Guitar appears quite simple at first, but a more attentive viewing reveals that the visual elements are highly synchronised to the music. Using precise video editing and computer generated graphics, Gondry was able to essentially assign many of the sounds to their own structures and objects. This synchresis, alongside the viewpoint of being inside a train, and the repetitive musical piece, provides a very hypnotic experience.

Ryoji Ikeda – Point of No Return

I experienced this installation in person at Eye Film Museum in Amsterdam. It is a simple, yet captivating work, using a stark contrast between a black circle and various strobed patterns, alongside noise and sine tones. The strobing, volume, and scale of the installation is intensely hypnotic, causing illusions similar to hallucinations when staring at the same point for an extended period.

United Visual Artists – Our Time

This is another installation I experienced in person, in Hobart in 2016. An array of lights swing and pulse slowly in various patterns, accompanied by slow droning and distant metallic impact sounds. The often circular motion of the pendulum-like light fixtures, accompanied by the ominous, low activation sound design, evoke a hypnotic state. Interestingly, across my multiple viewings of this installation, the presence of children running around and yelling didn’t detract from the multisensory experience.

Still image examples

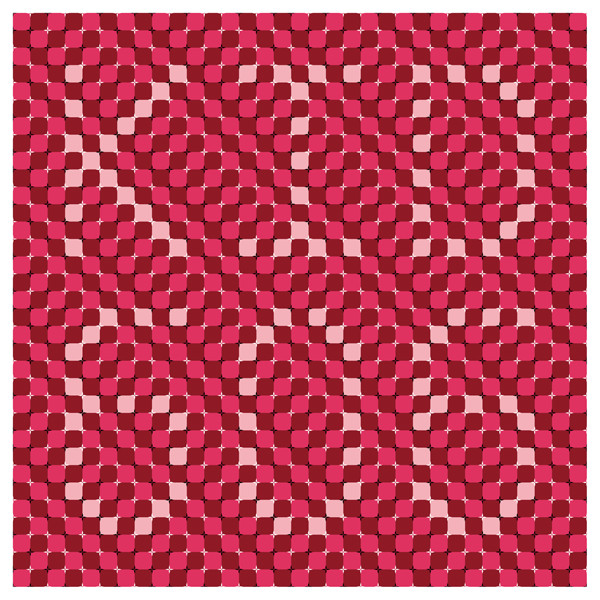

Kid606 – Sugarcoated album artwork

The use of an optical illusion on this album cover is something I would consider highly hypnotic, especially when combined with its accompanying audio content, as can be heard in the following excerpt from the track Forstevereichandjeffmills:

Simply scrolling up and down in the browser, or moving one’s eyes while looking at the cover is enough to give the illusion of movement. The almost sickening illusion is a key example of hypnotic visuals, in my experience. I do not necessarily want to make people sick, but it would be an interesting outcome.

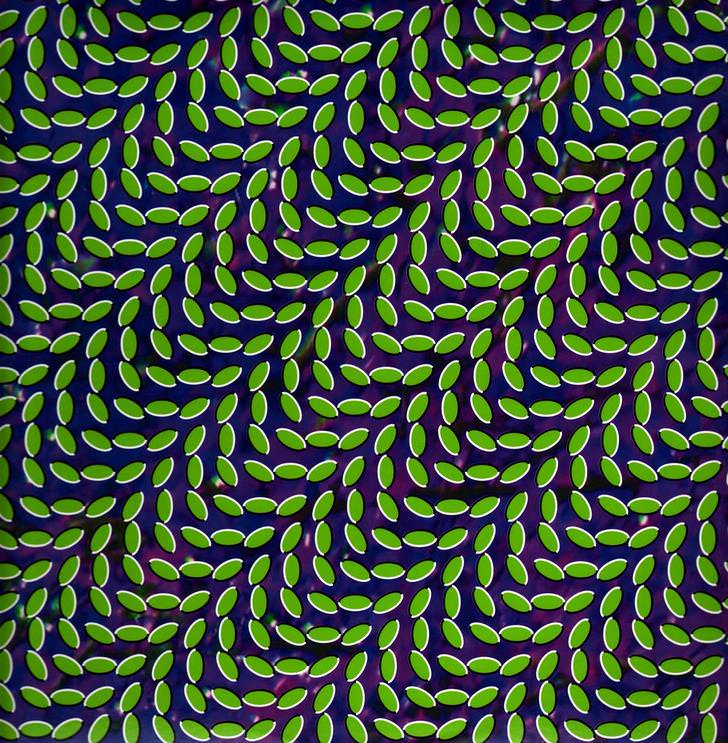

Animal Collective – Merriweather Post Pavilion album artwork

Similar to the Kid606 example above, this album artwork uses another optical illusion to invoke hallucinations. It’s another example of the music matching the hypnotic cover artwork:

Something I noticed about both images is the use of alternating black and white strokes, which seems to contribute greatly to the illusion of movement. This is something I would like to experiment with in my own work, perhaps in a browser-based piece.

Other examples

The Catacombs of Solaris interactive artwork

The Catacombs of Solaris is a first-person “game” where the player moves through a multicoloured world. However, upon changing direction, the world appears to be re-calculated, applying a screen shot of the previous perspective to the walls of the new world. It’s incredibly difficult to explain without directly experiencing the work, however, I believe it encompasses many of the other adjectives from this course, such as surreal, overwhelming, and even brutal at times. I personally find the ever-changing perspective to be a very hypnotic and captivating experience.

Audiosurf

Audiosurf is an interactive music visualiser / game that generates a course based on analysis of a provided audio file. It attempts to provide a similar experience to Guitar Hero, where the player obtains more points by collecting the coloured squares and avoiding obstacles. This is another example where the hypnotic experience is enhanced by the ending, where a phenomenon known colloquially as Guitar Hero tripping appears, resulting in a short period of time where the player’s vision appears to swirl or ascend.

Moire Illusion sculpture

The intersecting shapes and dual movement of this 3D printed sculpture imply more complex movement than is actually occurring, which is a technique I am highly interested in exploring. The sculpture could be considered an extension of the “classic” spiral hypnosis image, and given this connection, as well as the implied (and actual) movement, it provides a hypnotic sculptural experience, especially if produced at a large scale.

Satisfying Hexagons sculpture

Another 3D printed item, Satisfying Hexagons is a smaller, handheld sculpture controlled by a magnetic object held against the underside of the structure. The collapsing and expansion of each hexagon’s lines in relation to the others creates an illusion of 3D movement. Such perspective illusions and shifts can be considered hypnotic when repeated and controlled.

Further research

In curating the above examples, I’ve noticed a few interesting devices used which have parallels between audio and visual media. Notably, stark contrasts, quickly strobed, appear to have similar hypnotic effects in both audio and visual contexts. Additionally, spatial (audio) and perspective (visual) shifts could be employed to heighten the hypnotic effects.

A possible negative side-effect of exploring hypnotic experiences, particularly with regards to sound, is the potential for the work to be annoying or unfavourably repetitive. As such, I am also looking into studies covering misophonia.

I’ve bookmarked some articles and other media for further study:

Lotto, A & Holt, L 2011, ‘Psychology of auditory perception’, WIREs Cognitive Science, vol. 2, no. 5, pp. 479–489.

Watanabe, K & Shimojo, S 2001, ‘When Sound Affects Vision: Effects of Auditory Grouping on Visual Motion Perception’, Psychological Science, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 109–116.

Edelstein, M, Brang, D, Rouw, R & Ramachandran, V 2013, ‘Misophonia: physiological investigations and case descriptions’, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, vol. 7, p. 296.

Dennis, B 1974, ‘Repetitive and Systemic Music’, The Musical Times, vol. 115, no. 1582, pp. 1036–1038.

Samuel, A & Tangella, K 2018, ‘Sound changes that lead to seeing longer-lasting shapes’, Attention, Perception and Psychophysics, vol. 80, no. 4, pp. 986–998.

Nicolai, C 2010, Moire Index, Die Gestalten Verlag, Berlin, Germany.